1 Statics Review

All bodies and structures discussed in this text are assumed to be in static equilibrium, which means they experience no acceleration (the sum of all forces and moments are equal to zero). Any body that is not moving or that is moving at constant velocity is in static equilibrium. However, unlike in a standard statics course—where all bodies are assumed to be rigid—in this text bodies are expected to be deformable. This means they may stretch, contract, twist, bend, break, buckle, and so on. To determine how an applied loading situation affects a given body or structure—and potentially causes it to deform—we must first apply statics to establish the distribution of forces and moments within the body. This is the first step of many problems. This chapter reviews those aspects of statics that are prevalent throughout this course.

Section 1.1 reviews the concept of external loads and their representation on free body diagrams.

Section 1.2 reviews equilibrium of structures in two dimensions, including analysis of two-force members and multiforce members.

Section 1.3 addresses internal loads, including normal force, shear force, and bending moment.

Section 1.4 reviews equilibrium in three dimensions.

1.1 External Reactions and Free Body Diagrams

Click to expand

External forces and moments are those that act on the boundaries of a system. They include loads applied to the main structure (weight, wind, pressure, etc.) and the reactions these loads induce in supporting elements (pins, rollers, welds, etc.). In the case of external reactions, the term reaction refers to the forces and/or moments exerted by the supports on the body in response to the applied loading to maintain equilibrium.

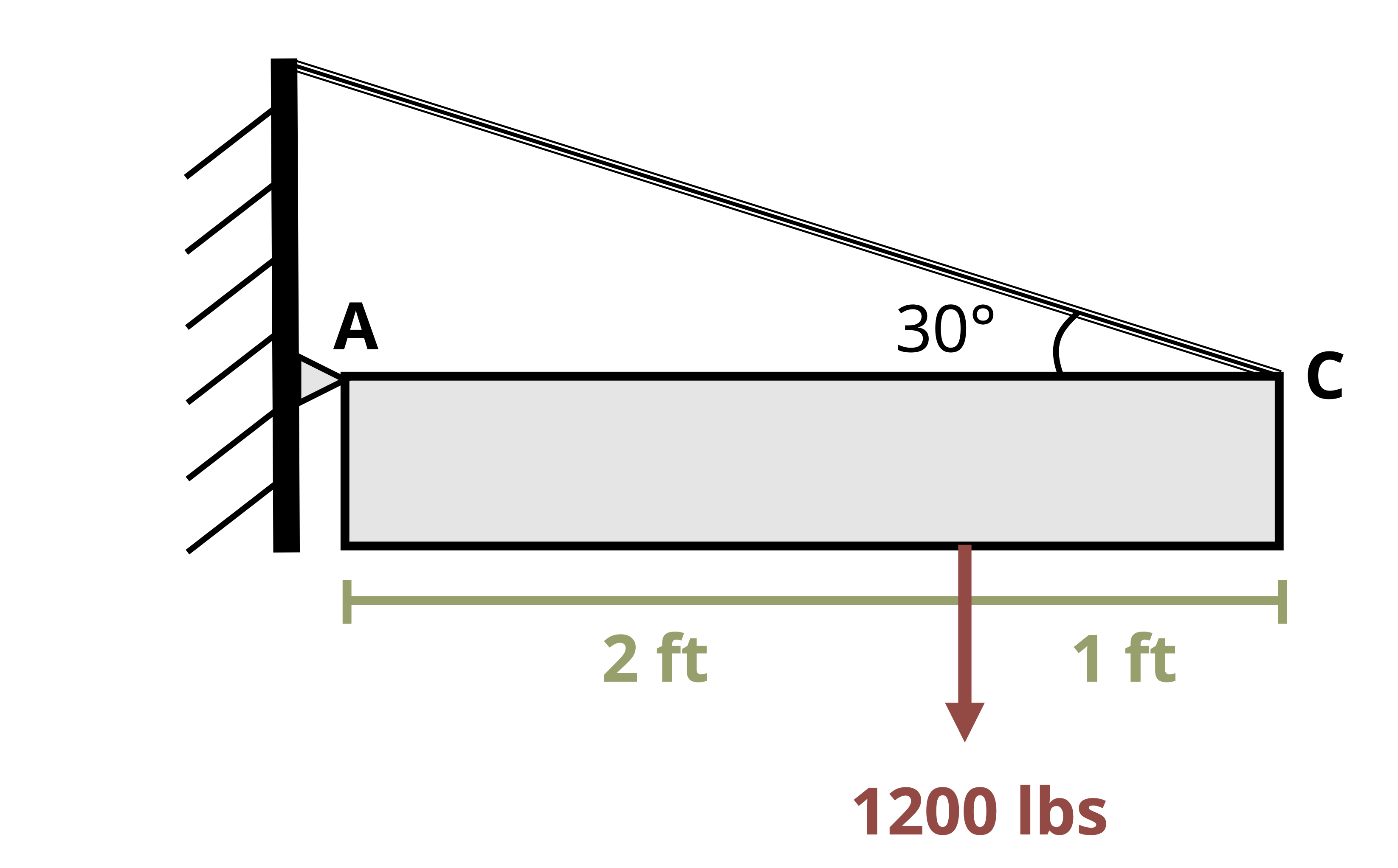

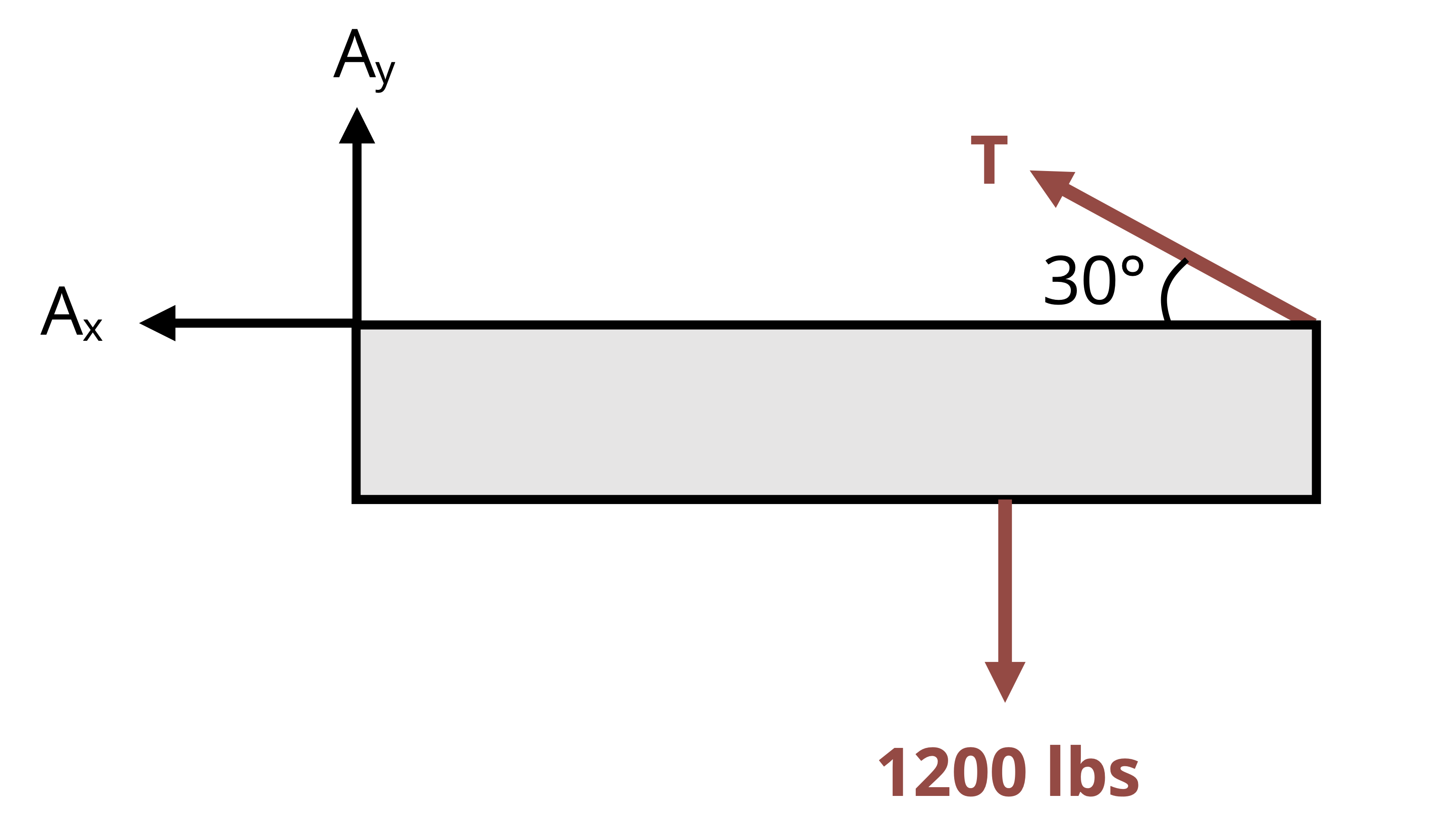

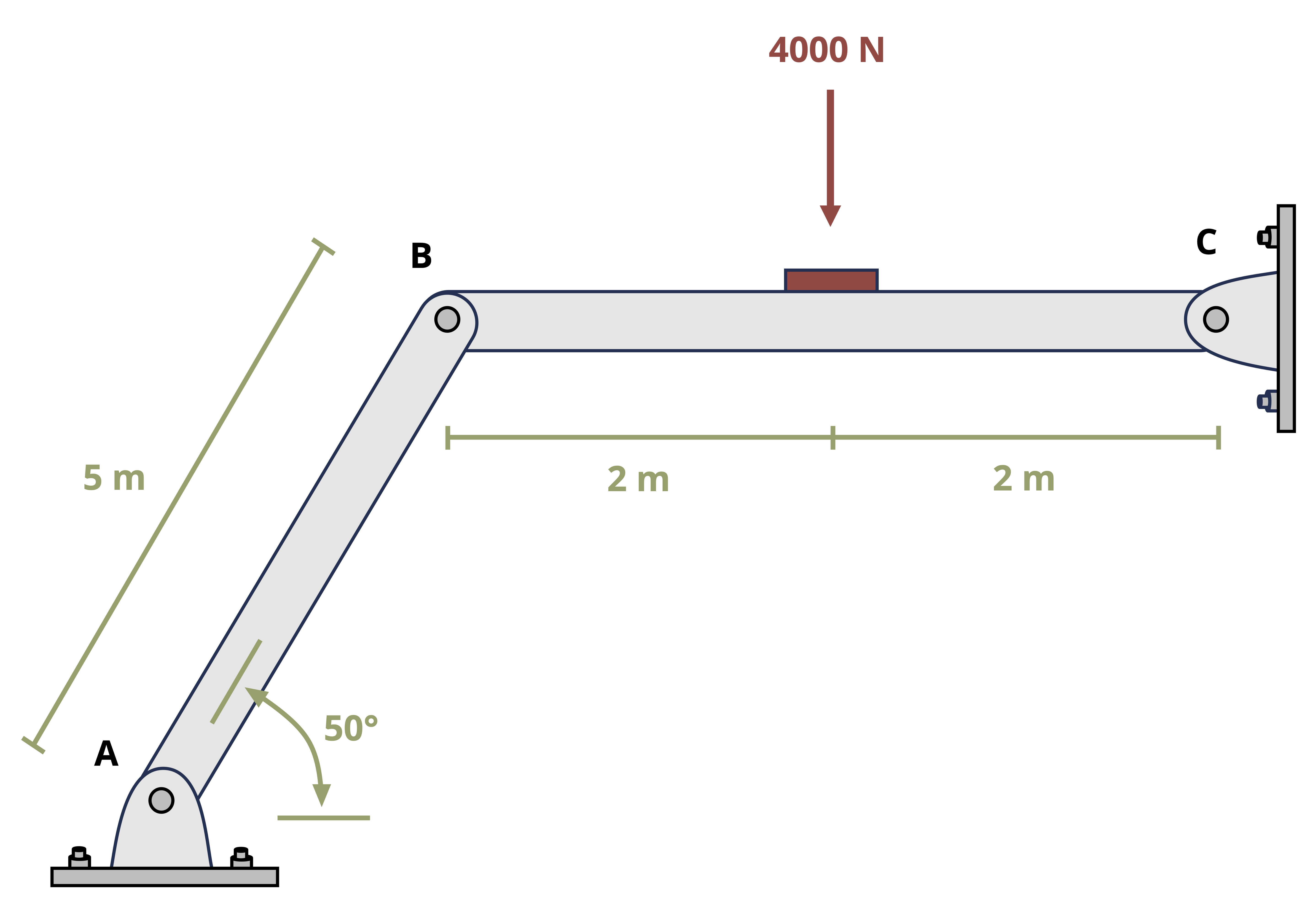

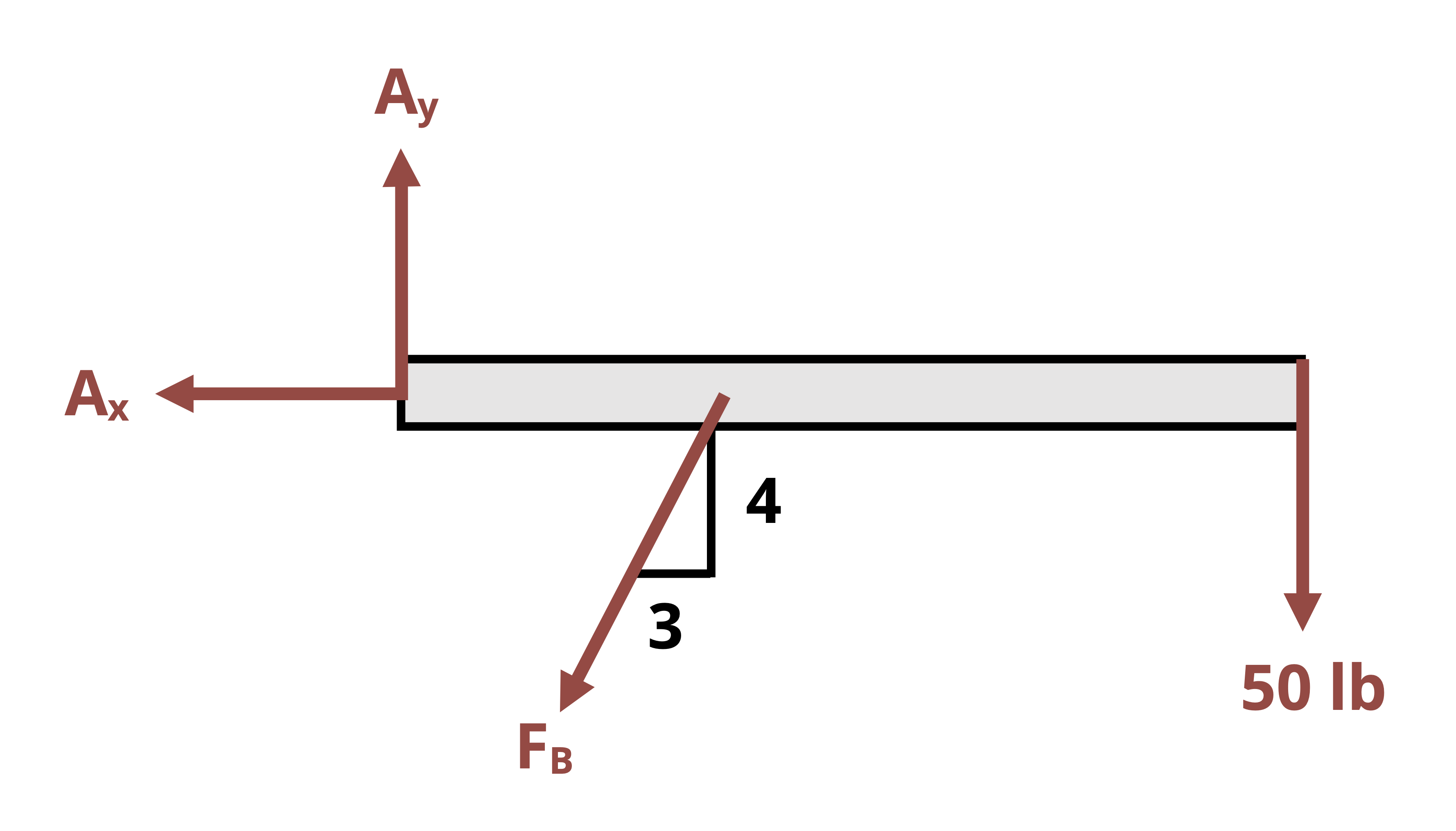

Finding the external reactions is the first step in many of the problem types covered in this text. This process begins with drawing a free body diagram (FBD) of the body. An FBD is a sketch of the body “freed” from its supports, showing all the applied and reaction forces and moments to be considered in the analysis. In cases where some loads are insignificant compared to others (e.g., weight sometimes falls into this category), those loads are omitted from the FBD.

The importance of drawing FBDs as a first step in calculating internal and external loads and reactions cannot be overstated. Creating these diagrams establishes which loads and reactions are being included in the analysis, as well as their assumed directions. With the diagrams prepared, you can maintain consistency when summing forces and moments to apply equilibrium equations, helping to ensure accurate results.

Some commonly encountered supports, along with their corresponding reactions and FBD representations, include the following:

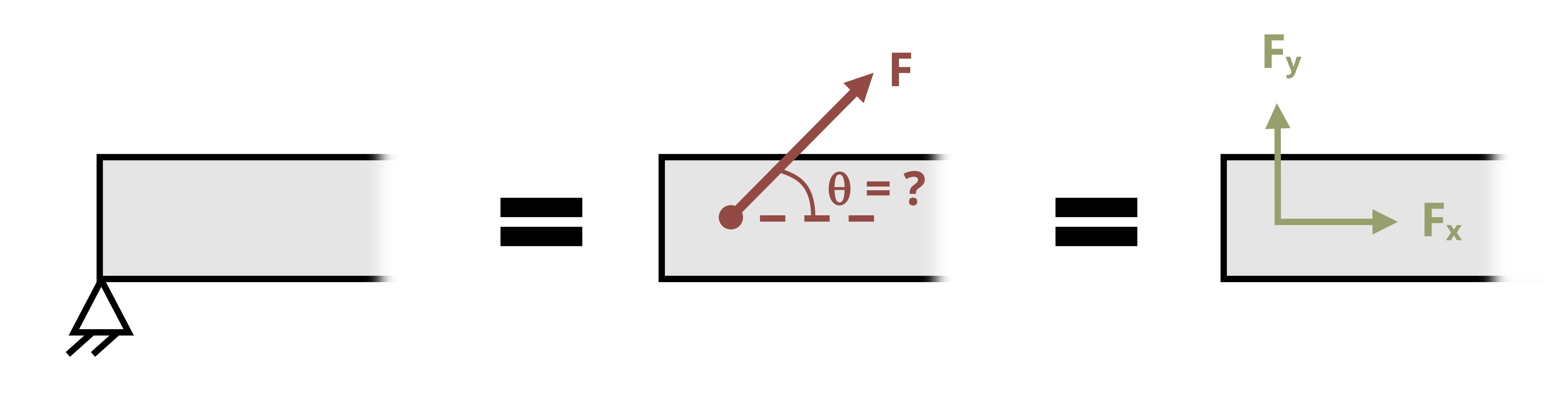

- Pin supports: Pin supports resist any lateral movement of the body relative to the pin at its location. The direction of the overall reaction force (F) is generally unknown, so it is represented as a set of perpendicular force components (Fx and Fy) in the figure below but may also be represented as any set of perpendicular components.

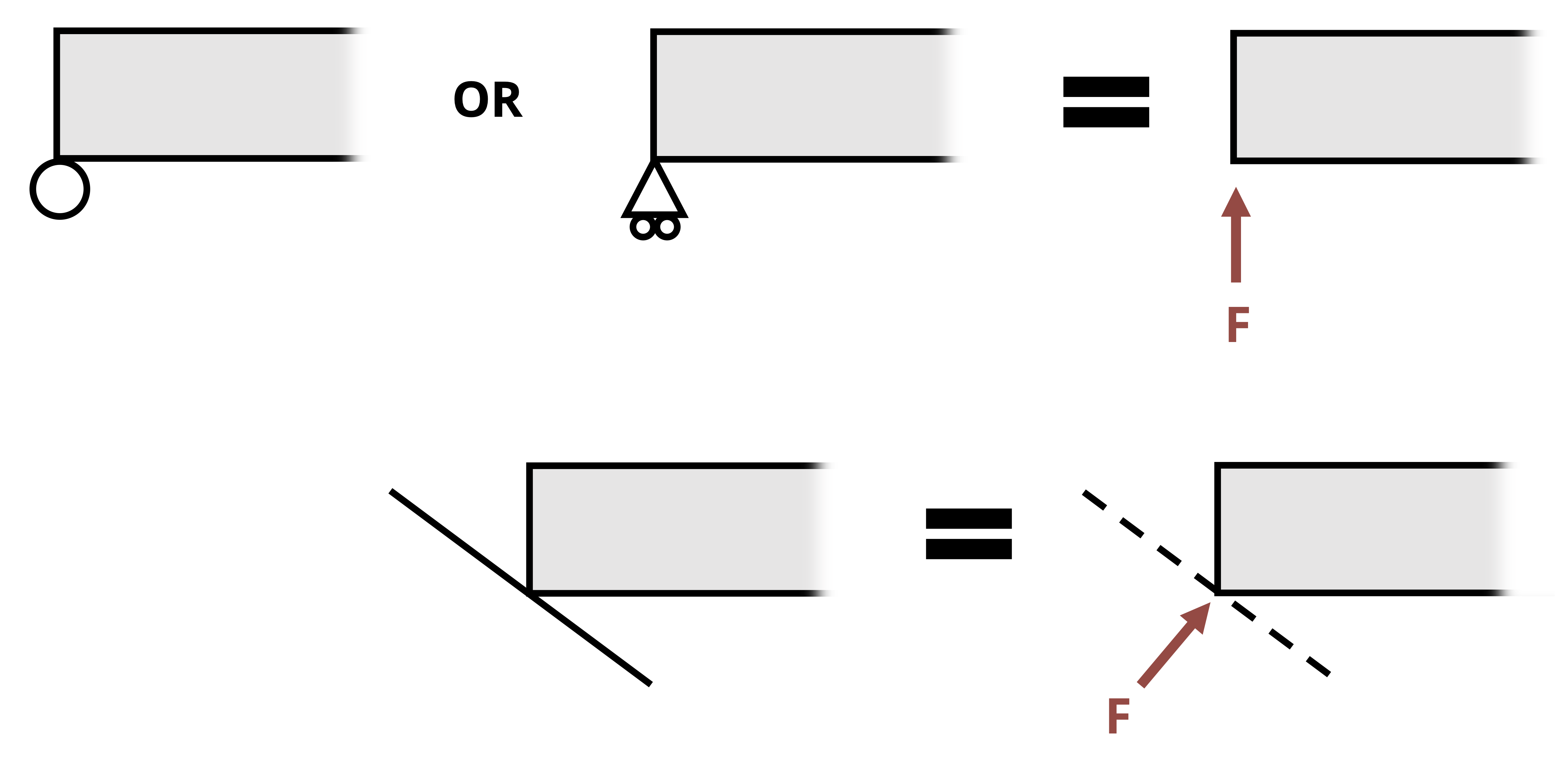

- Normal supports: Normal supports generally consist of surfaces on which the body simply rests (like a beam on a roller) and/or supports that are not fixed to any other surface (like a rocker). Similar to pin supports, normal supports prevent movement of the body relative to the support at its location. However, unlike pins, normal supports prevent only movement in the direction normal to the support site. Consequently, the reaction force (F) acts strictly perpendicular to the supporting surface.

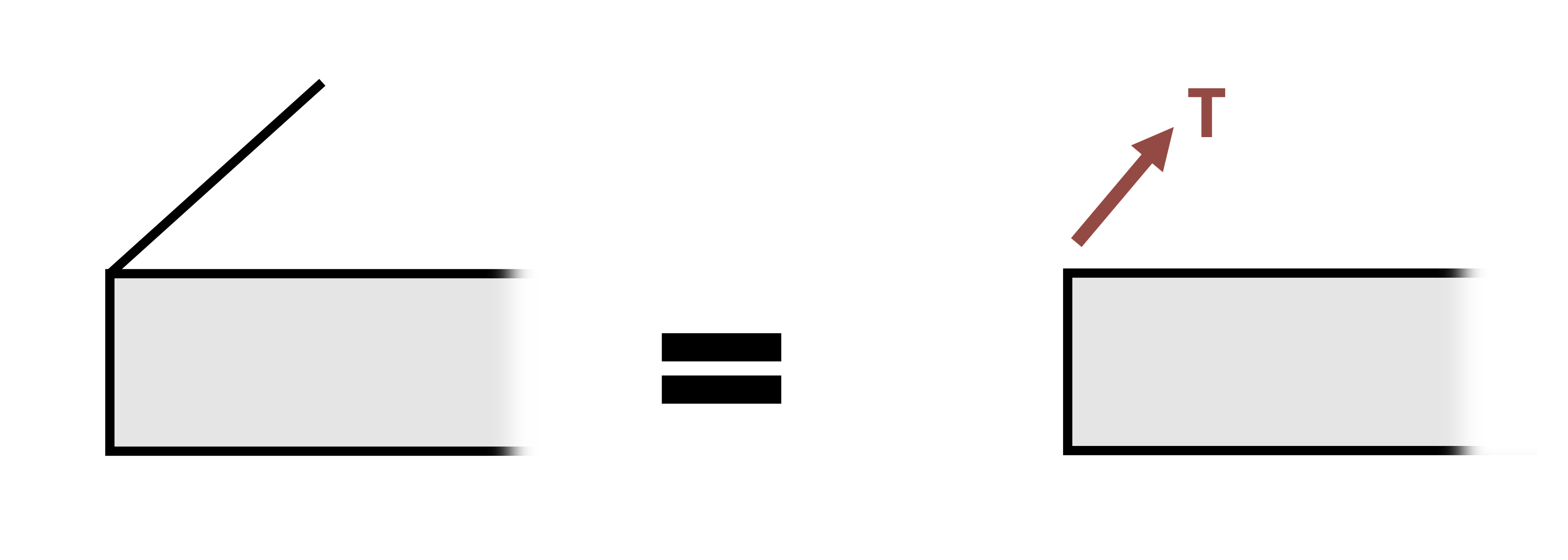

- Cable: A cable provides a tensile force reaction (T). It pulls on the body but never pushes. The reaction force acts in a direction along the path of the cable, extending away from the body and toward the external attachment point.

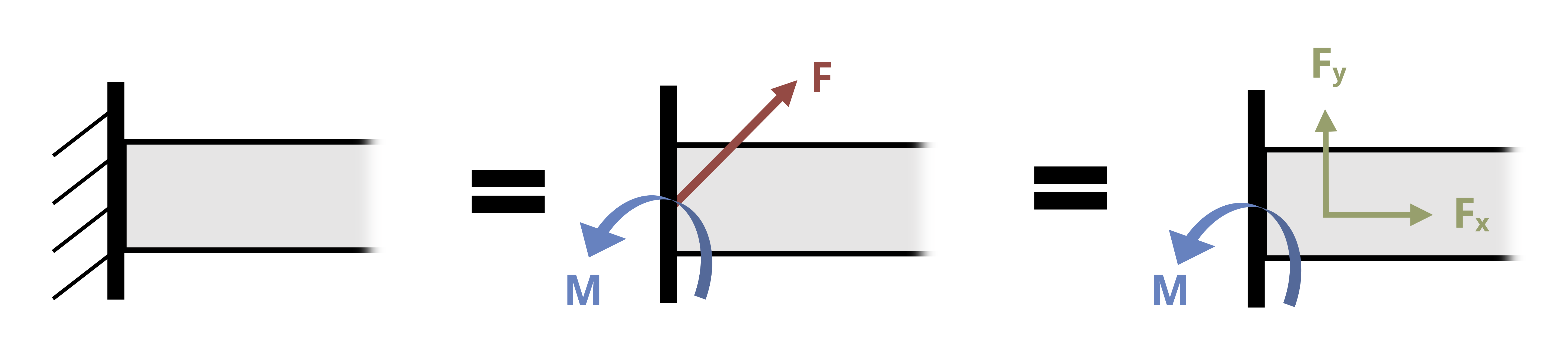

- Fixed support: A fixed support is capable of resisting both lateral movement and rotation, so its reactions consist of a reaction force (F) and a reaction moment couple (M). As with the pinned support, the direction of the overall reaction force is not necessarily known and is therefore represented by a set of perpendicular components. It is important to remember that the reaction moment couple to be solved for is an unknown, just like the reaction force components, and must be included in the moment equation about any point on the body.

Note that when components of the reaction force are found individually, as with the pin support and fixed support, the overall magnitude of the force (F) can be calculated as

\[ F=\sqrt{F_x^2+F_y^2}\text{.} \]

Its direction (i.e., angle measured from the horizontal axis) can be calculated as

\[ \tan \theta_x=\frac{F_y}{F_x}\text{.} \]

Note how the FBDs are drawn in the examples provided throughout this chapter. Geometrical details of a body—such as lengths and angles—are often included on FBDs. However, in this text these features are frequently excluded because they are provided in the problem statement, and the focus here is on representing the loading. You should keep in mind that in some courses and with some instructors these geometrical details may be considered required features of FBDs.

1.2 Equilibrium in Two Dimensions

Click to expand

Once the FBD is drawn, the next step is to apply the equilibrium equations. In two dimensions (x-y plane) these are

\[ \begin{align} \boxed{\sum F_x=0 \quad\sum F_y=0 \quad \sum M_{any~point}=0} \end{align} \tag{1.1}\]

A review of finding moments is given in Section 1.4.

Since there are three equations, a statically determinate problem should have no more than three unknowns.

Example 1.1 illustrates the process of finding external reactions.

1.2.1 Two-Force Members

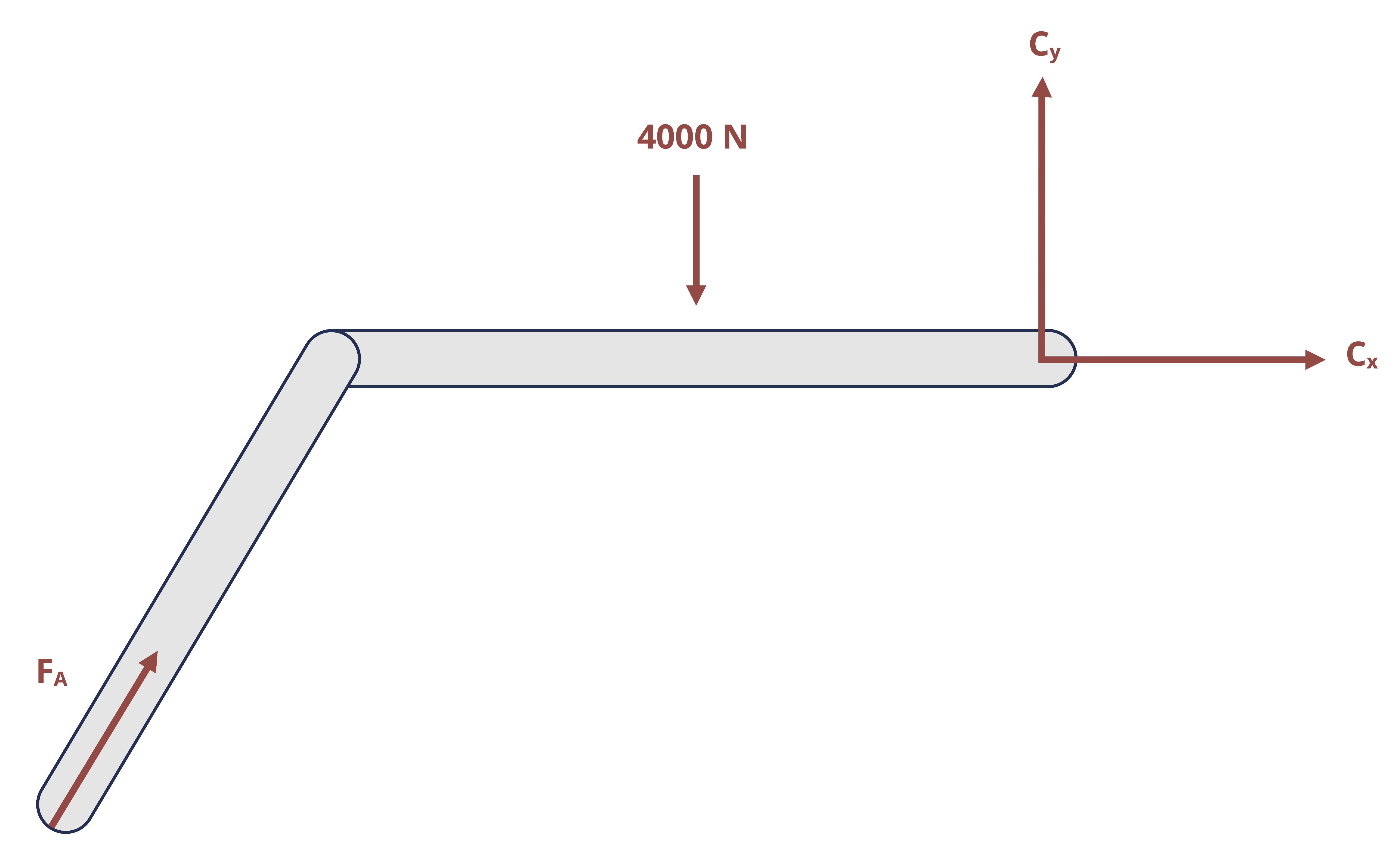

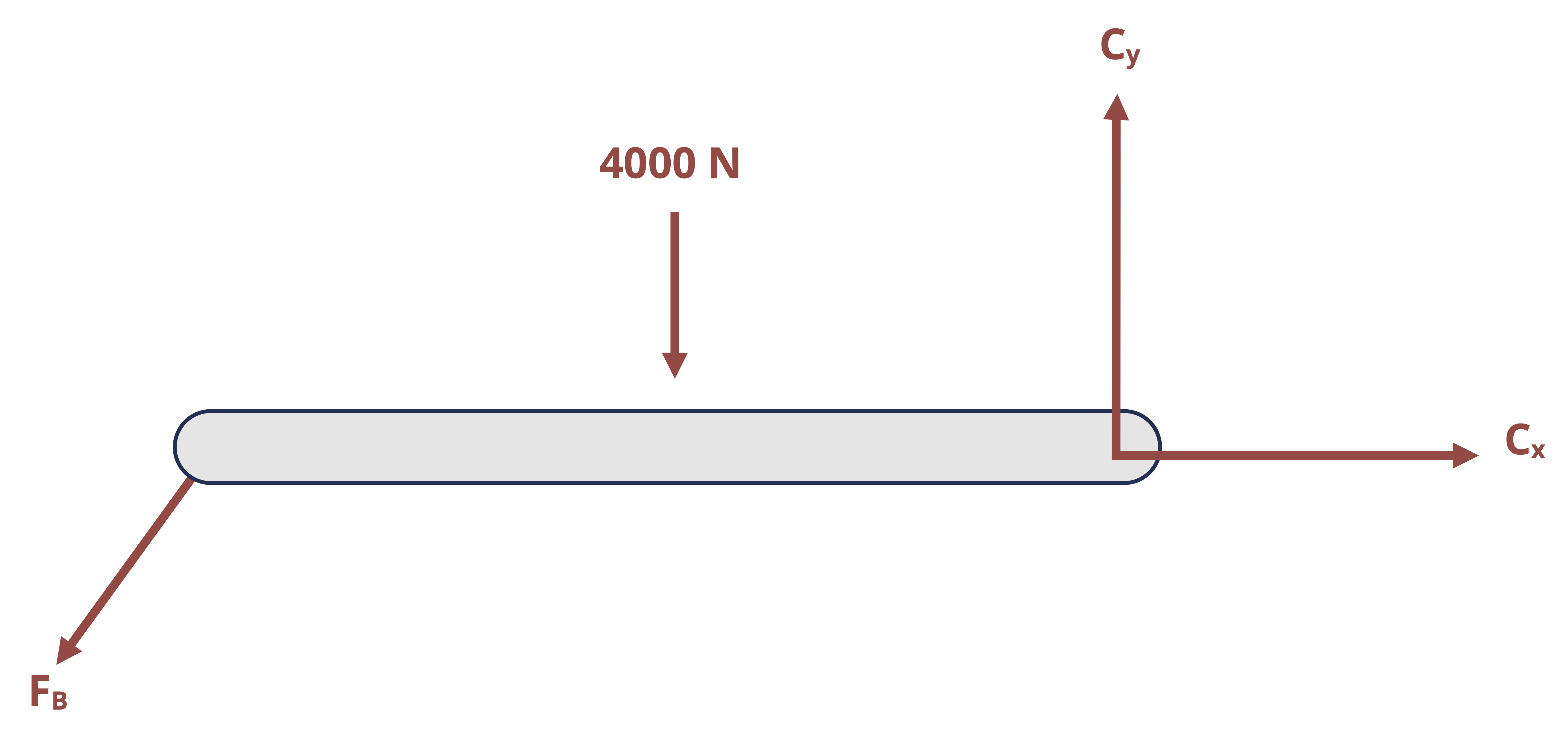

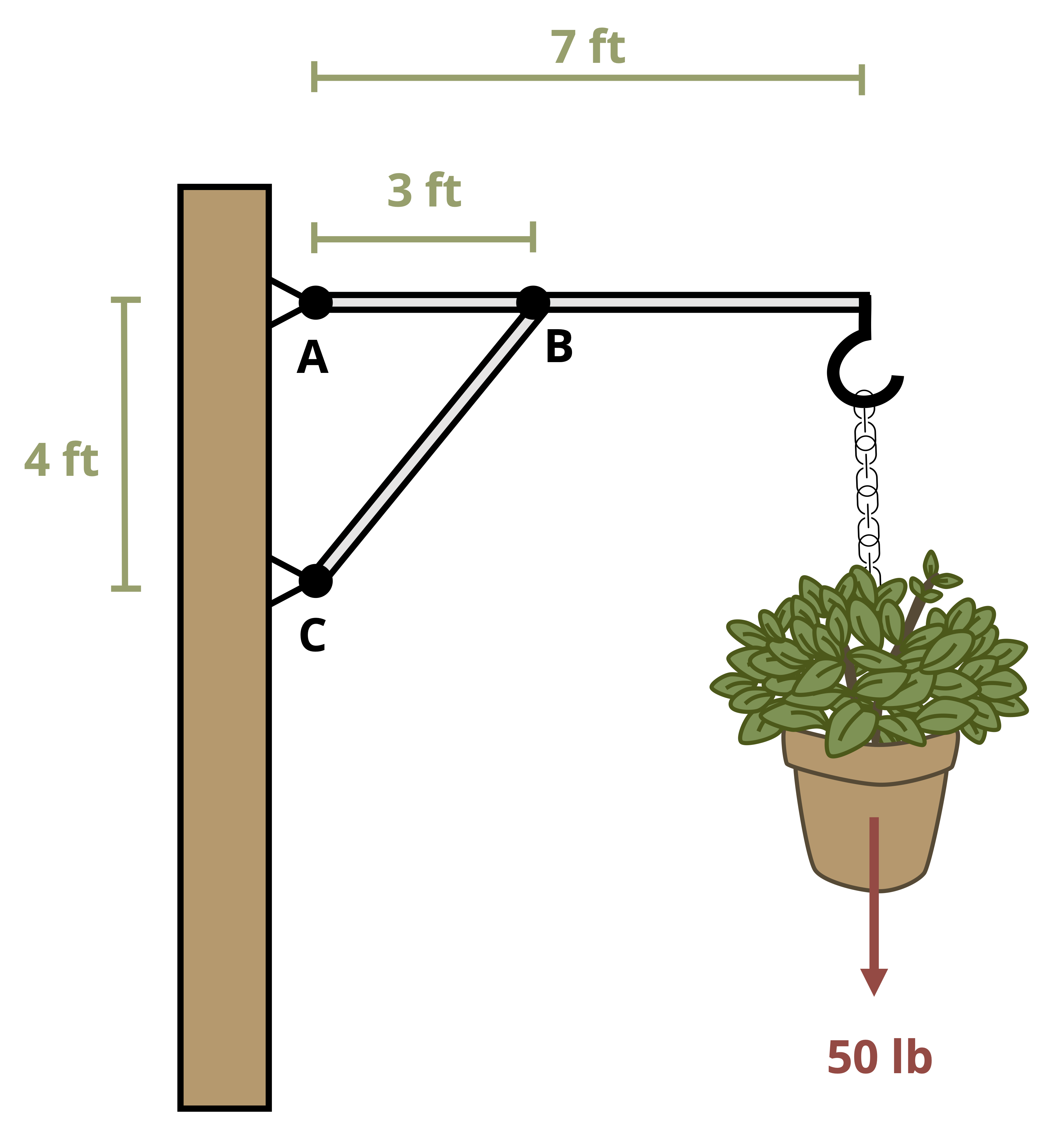

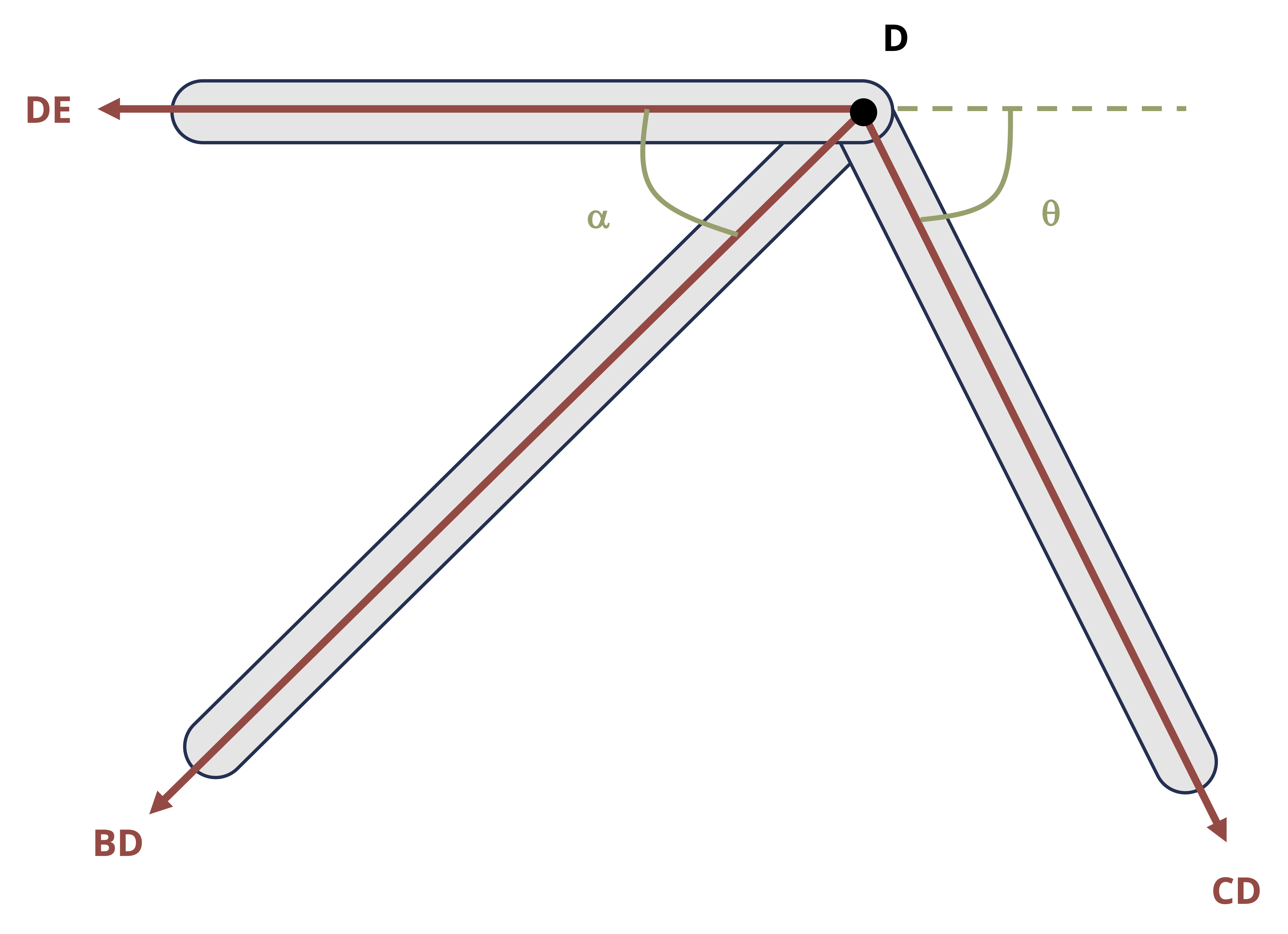

One special type of pin connection for which the direction of the reaction force is known is one in which the pin is connected to a two-force member. Contrary to its name, a two-force member is not necessarily a member on which only two forces act. Rather, it is a member where forces are applied at only two distinct locations regardless of how many forces there are. A two-force member can have any shape, as is demonstrated in Figure 1.5. One easy way to recognize a two-force member is by noting the presence of only two pinned points and no other locations where a force or moment couple is applied. Once a member is identified as a two-force member, it can be concluded that the resultant force at both pins is equal in magnitude (FA = FB in Figure 1.5), is opposite in direction, and follows a line of action that goes through the pins. For a straight member, the internal force (discussed in Section 1.3) is equal to the reaction force in the pin.

The presence and recognition of two-force members simplifies equilibrium calculations by reducing the number of unknowns before any computations are performed. This is demonstrated in Example 1.2.

1.3 Internal Reactions

Click to expand

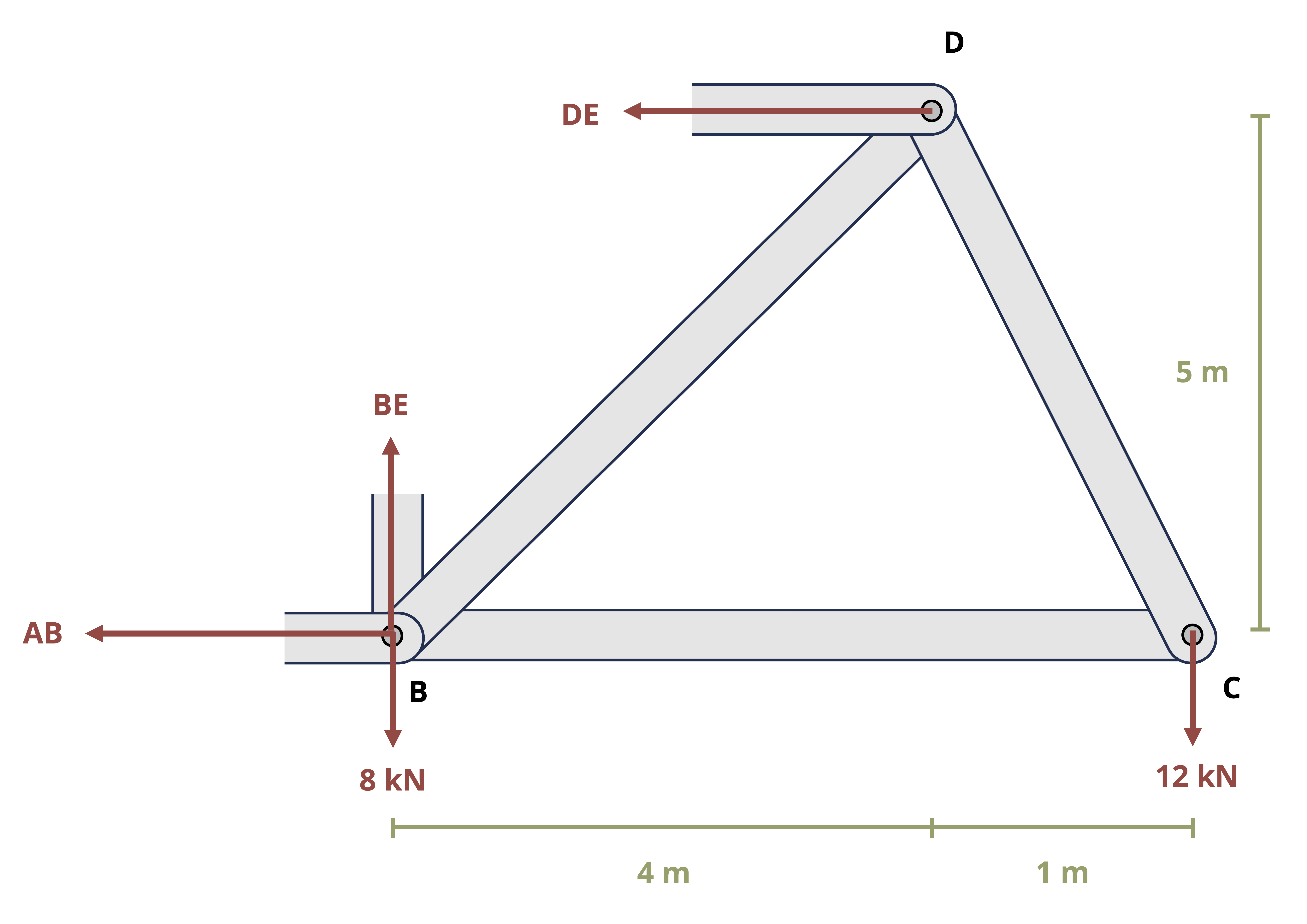

Internal reactions can be forces and moments at connection points between members (e.g., pins connecting multiple members of a frame, machine, or truss), as well as reactions at any point in a continuous body (e.g., a point in the middle of a beam). These reactions are the forces and/or moments necessary to hold a structure or a body together and are ultimately the loading aspect needed to determine if and how a body will deform or even break.

1.3.1 Internal Reactions at Pinned Connections

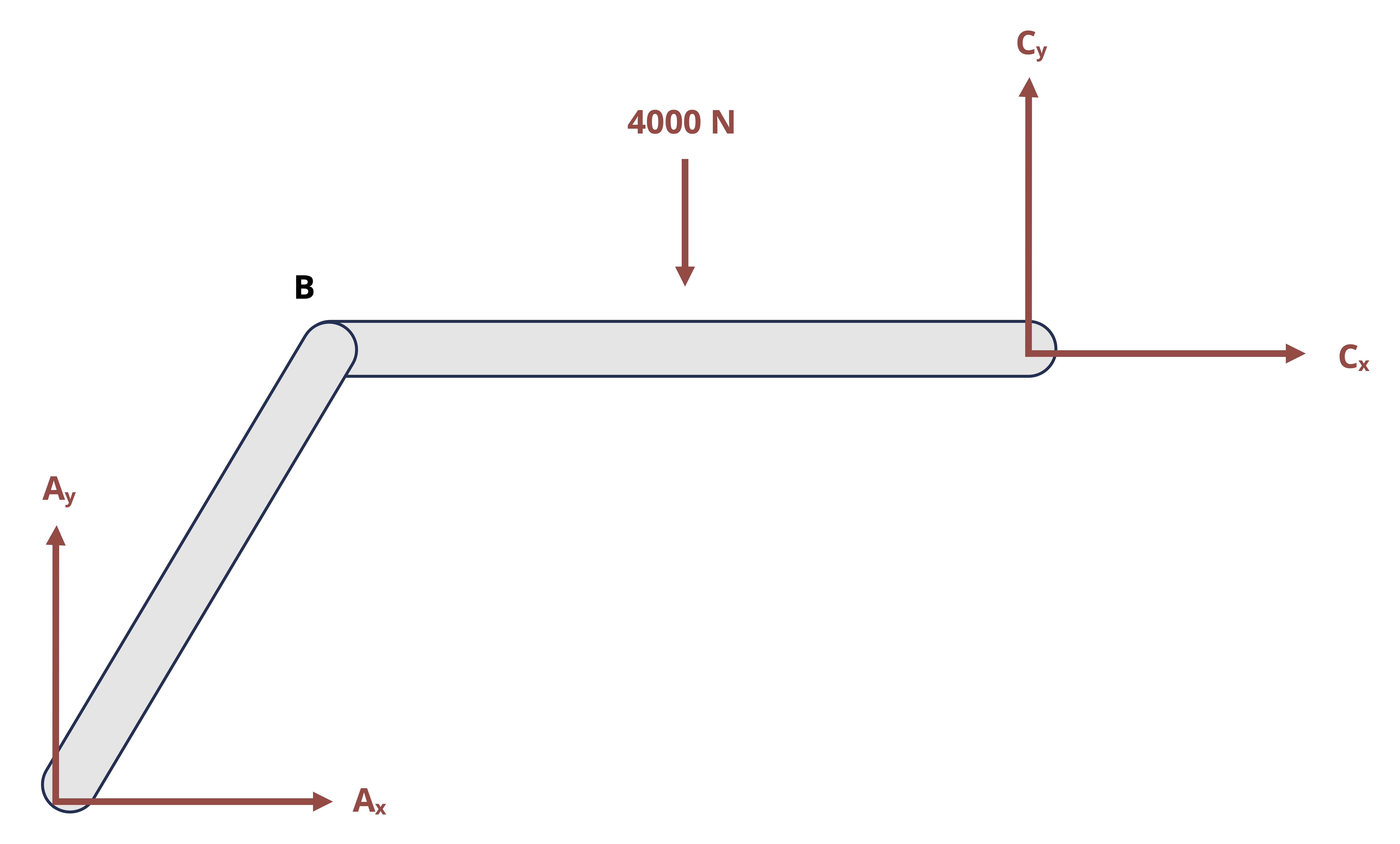

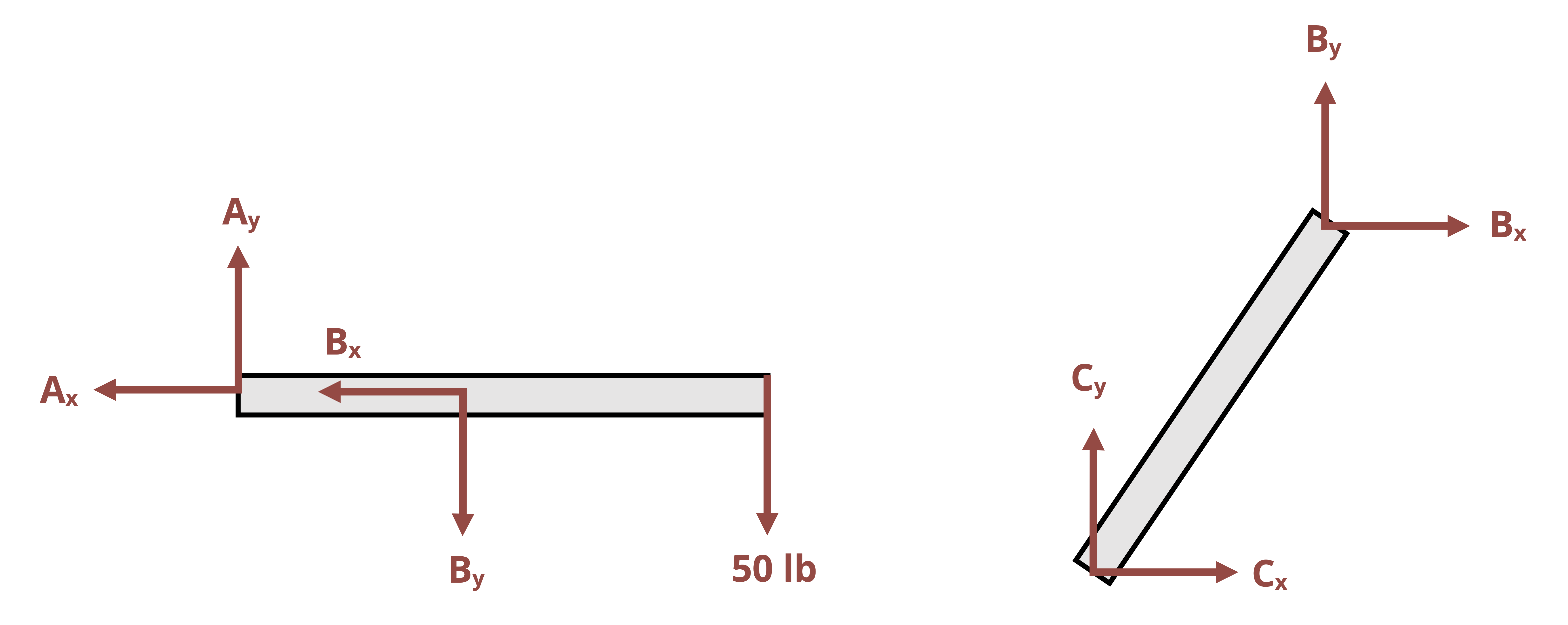

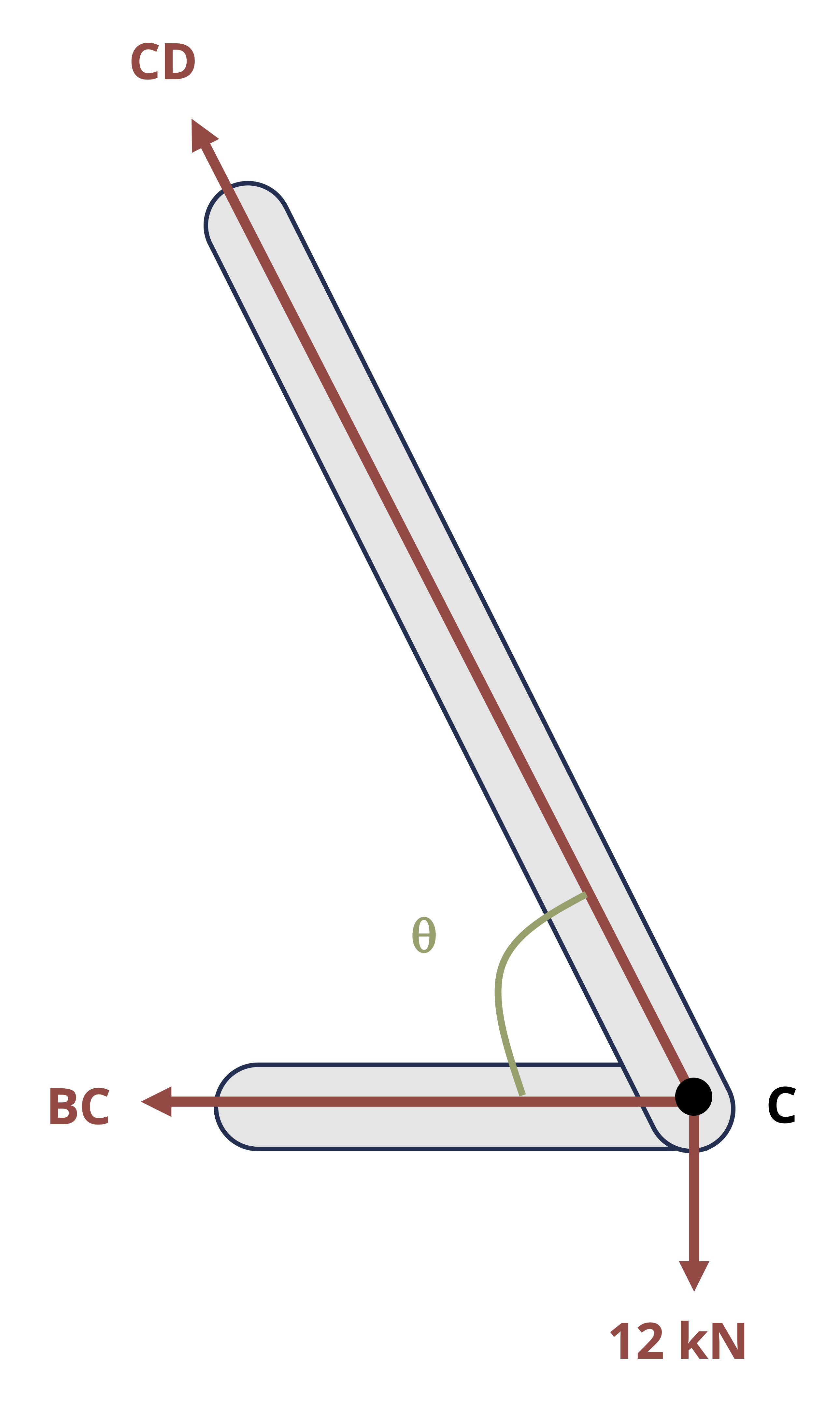

An FBD of an entire structure consisting of connected members omits the forces at the connecting pins because the connected members exert equal and opposite forces on each other, and these forces cancel each other in equilibrium equations. The pins that connect the members nonetheless experience reaction forces you must determine to ensure the integrity of the structure. Do the following to find the reaction forces in these internal pins:

Prepare the individual members’ FBDs (imagine the pins pulled out and consider each member separately). With the members disconnected, the reaction forces at the connecting pins no longer cancel each other out in equilibrium equations applied to the individual members. The reaction forces are drawn on the FBDs in the same way as for support pins, described in Section 1.1.

- However, since the connected members do ultimately exert equal and opposite forces on each other, the reaction forces of pins common to two members are drawn in opposite directions on these members’ FBDs.

Given the FBDs, write and solve equilibrium equations for each body. Because three equilibrium equations can be determined for each FBD drawn, one could theoretically solve for three times the number of unknowns.

Note that the FBD of the whole structure may be useful to help solve for some unknowns.

In addition, as discussed, when one of the connected members is a two-force member, the reaction at the pin runs through the points where the forces act on the two-force member.

Example 1.3 and the alternative method used for Example 1.2 demonstrate these concepts.

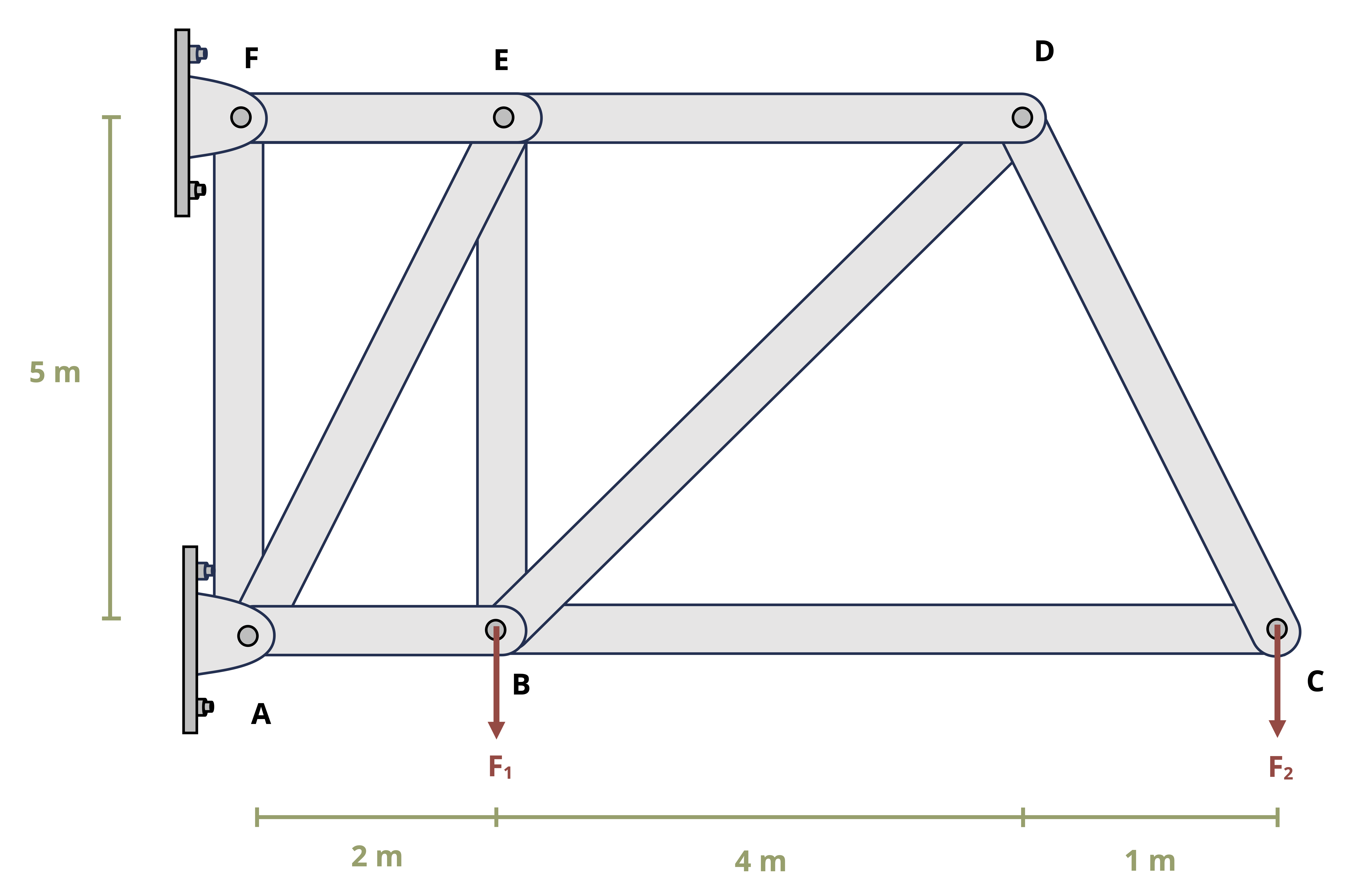

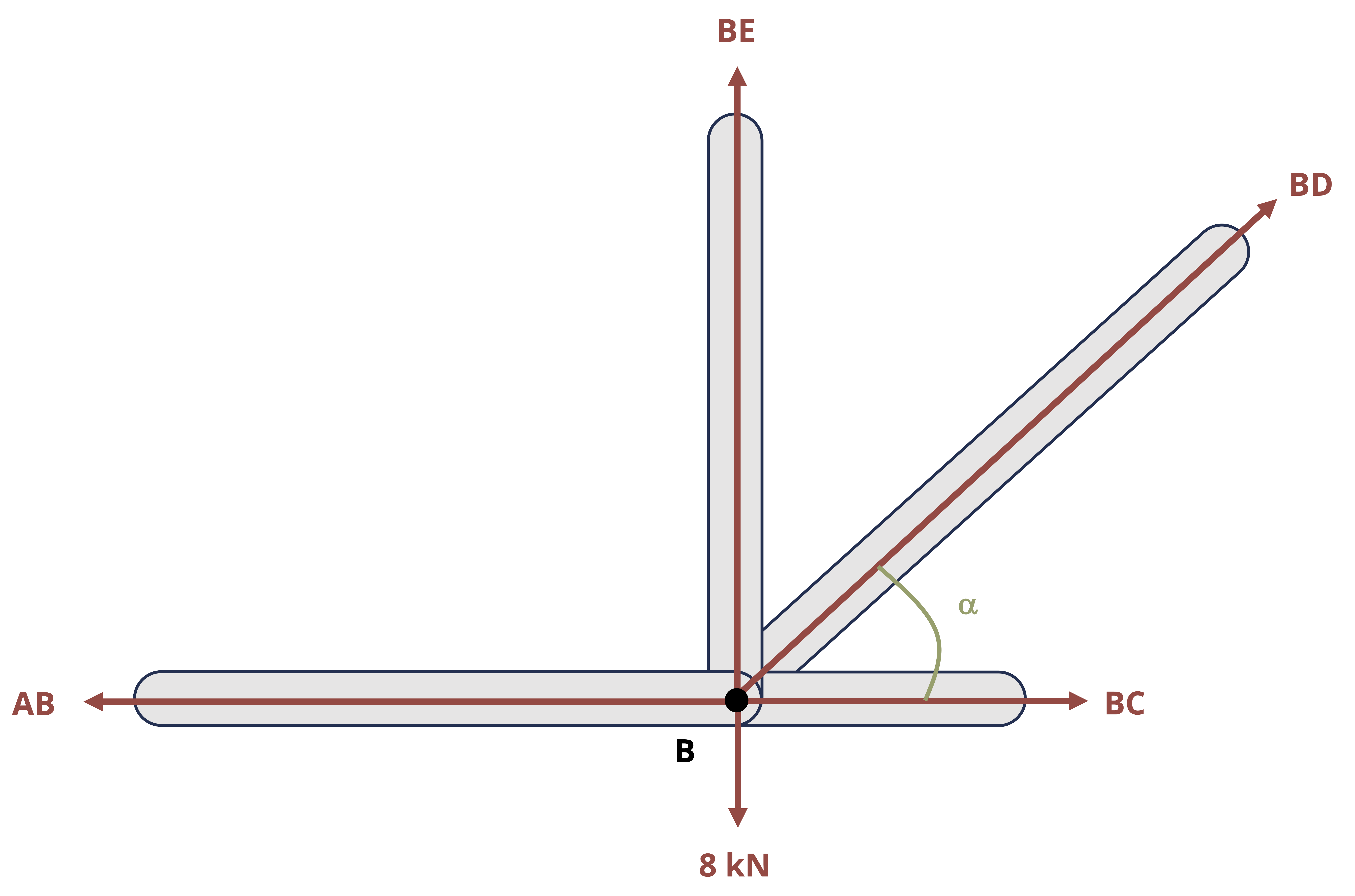

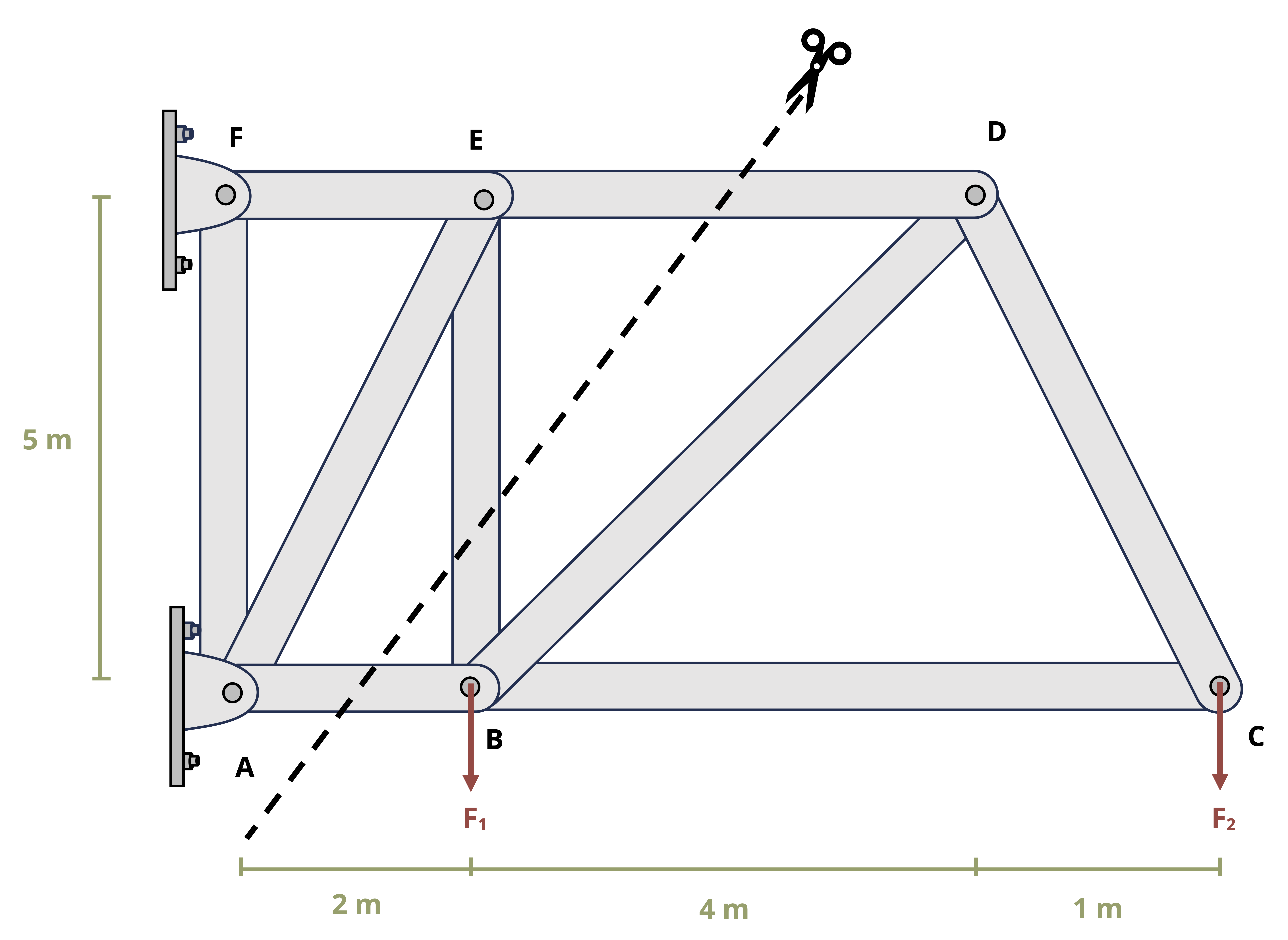

1.3.2 Internal Reactions in Truss Structures

Truss structures are made up of only two-force members. The two main methods of determining internal reactions in planar (2D) truss structures are method of joints and method of sections. In using method of joints, we draw an FBD of the connecting pins (joints) within the truss. Since all the members connected at any given pin will be two-force members, the reactions can be drawn in known directions. However, because the forces all pass through the same point on the body, the moment equilibrium equation is not useful, so only the forces equilibrium equations can be used for each joint. This means that only two unknowns can be solved for at each joint. The method of joints is most useful when the forces of all the truss members are sought or when the only forces sought are attached to a joint with only two members.

To use method of sections, we cut through the truss structure and with the FBD analyze the intact part of the structure either to the left or to the right of the cut. The FBD of either side will show the applied forces and the reaction forces from the cut-through members. These reactions will be equal in magnitude but opposite in direction between the two sides of the cut. The side to examine is usually that which will not require finding external reactions (if there is a free end to the truss) and/or is least complicated to deal with in terms of geometry or applied loads. All three equilibrium equations can generally be effectively applied with method of sections, so three unknowns can be solved for with any given cut. Keep in mind that moments can be taken about points that lie outside the isolated section, which can lead to more efficient solutions.

Example 1.4 demonstrates the use of method of joints and method of sections to solve for forces in truss members.

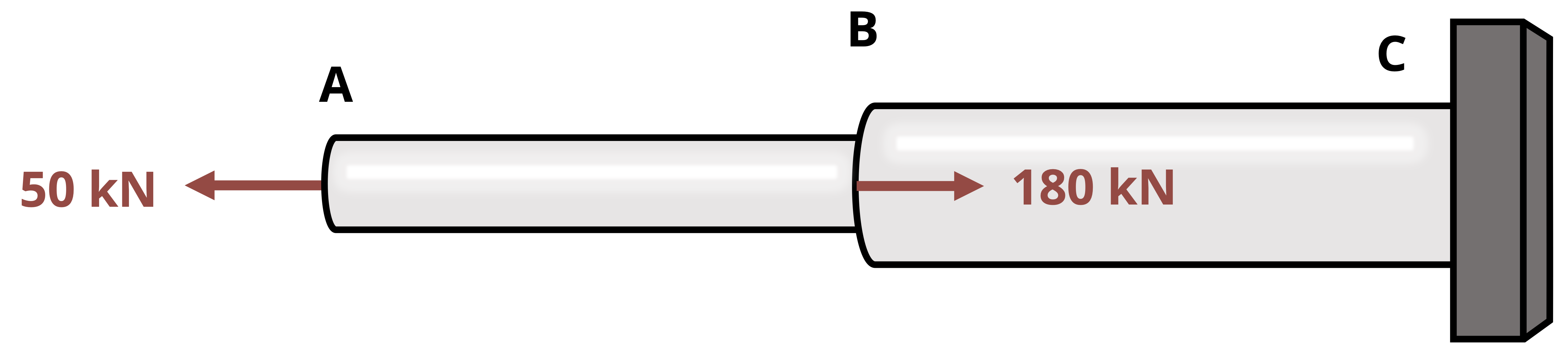

1.3.3 Internal Reactions in Continuous Bodies

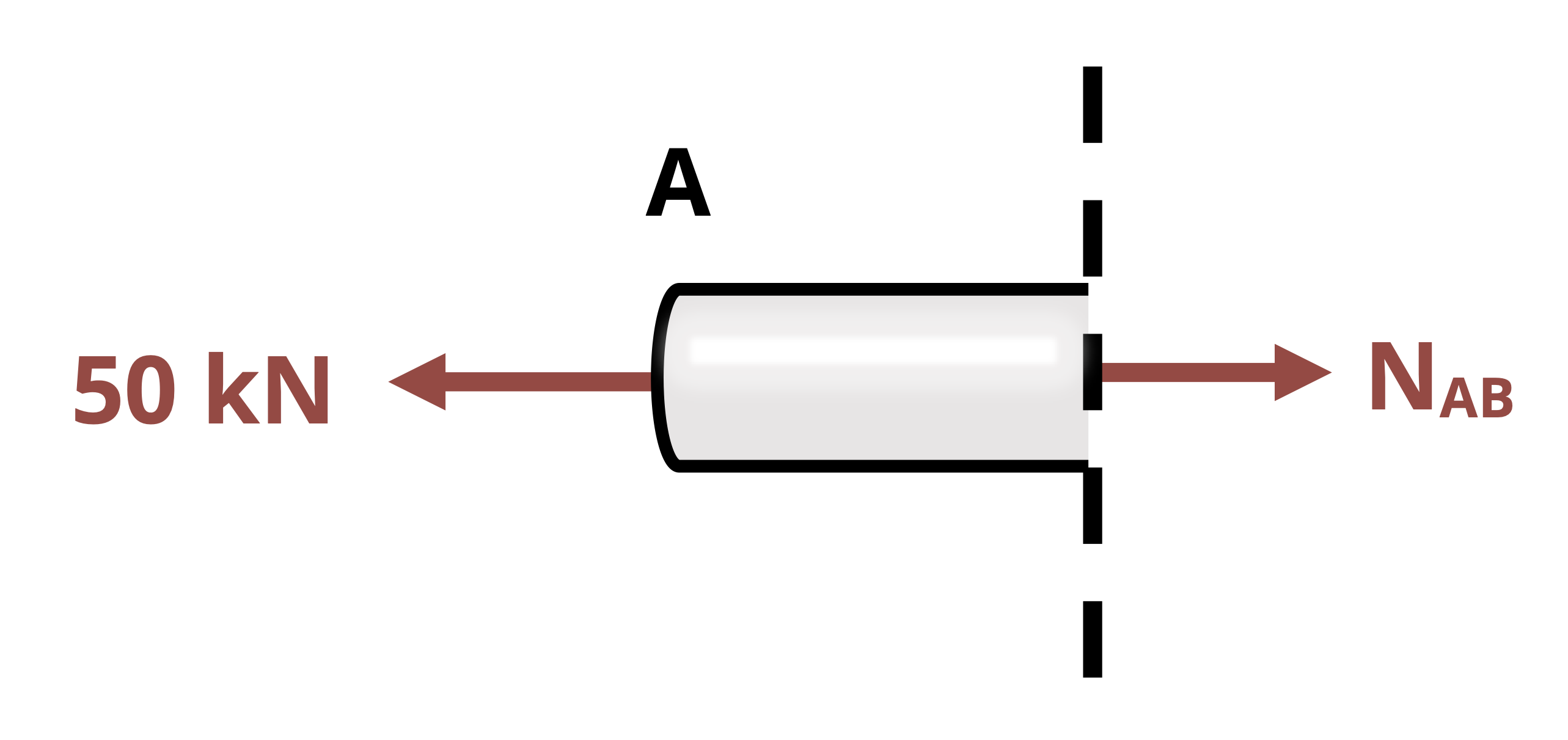

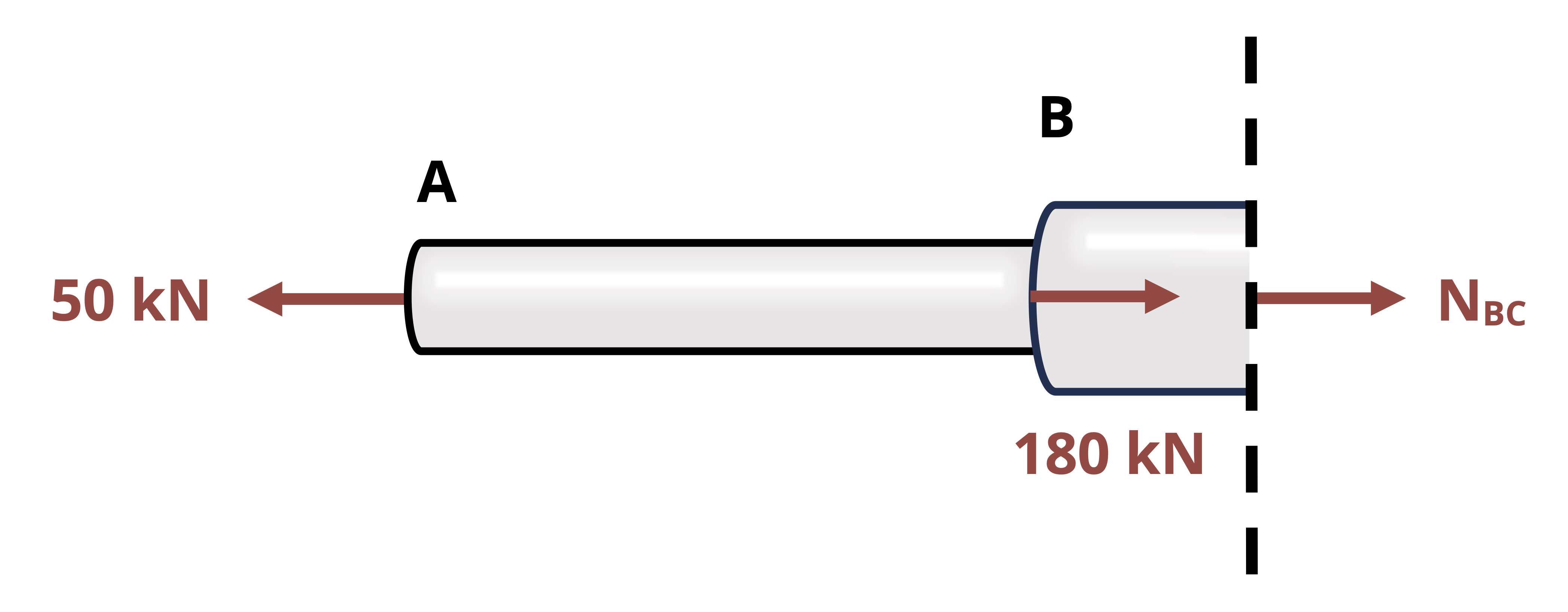

Internal reactions also exist within a body or structure. These reactions are necessary to hold the body together and vary from point to point in a body depending on the distribution of external loading. As shown in Figure 1.6, the reactions at any given point can be examined by making a cut at the point of interest in the body. Think of any point within a body as acting as a fixed support for the rest of the body. That is, every point must potentially exert a force parallel to the cross section where the cut is made, which is the shear force V; a force perpendicular to the cross section where the cut is made, which is the normal force N; and a reaction moment where the cut is made, which is the bending moment M. Moreover, as discussed for internal pin reactions and the cut made for method of sections for trusses, the reactions at a cut will be equal and opposite on the two sides of the cut.

To determine the reactions, draw and use the FBD of the part of the beam either to the left or to the right of the cut. As with method of sections for trusses, choose which side of the cut to examine primarily by determining which side appears easiest and most efficient to analyze. Once the FBD of the cut section is drawn, the three equilibrium equations can be applied to determine the internal reactions. The determination of shear and bending moments in beams is reviewed in more detail in Chapter 7. The focus of Example 1.5 is on the determination of the normal force, as this is important in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3.

1.4 Equilibrium and Reactions in Three Dimensions

Click to expand

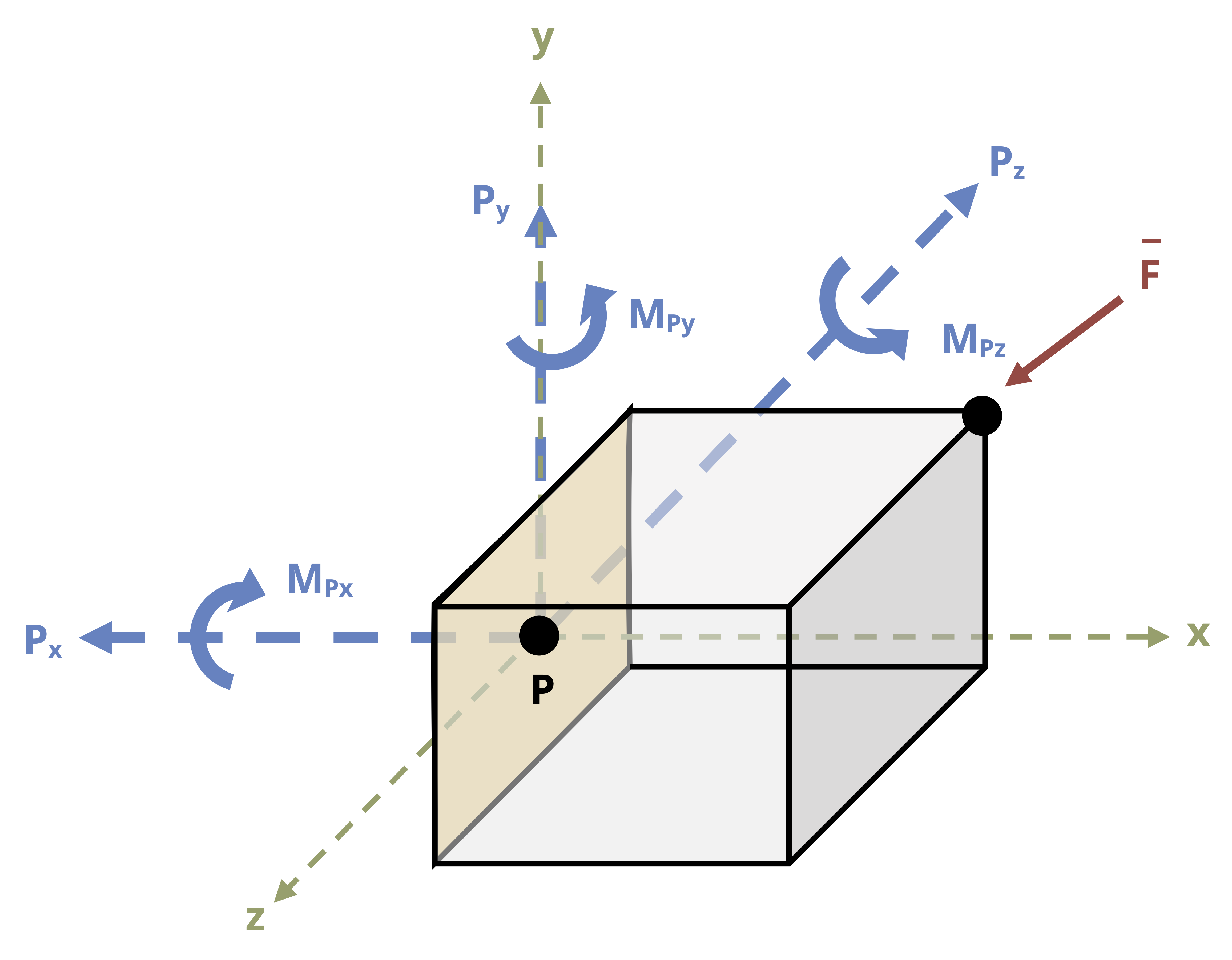

While we can often model structures as two dimensional, as in the previous examples, many real-life structures are subjected to forces and moments in all directions, necessitating the consideration of three-dimensional forces and three-dimensional moments. The process of finding external and internal reactions is the same in 3D as in 2D, but there are three additional equilibrium equations and three additional reactions.

For 3D systems there are six total scalar equilibrium equations as shown.

\[ \boxed{\begin{array}{ll} \sum F_x=0 &\;\;\; \sum M_x=0 \\ \sum F_y=0 &\;\;\; \sum M_y=0 \\ \sum F_z=0 &\;\;\; \sum M_z=0 \end{array}} \tag{1.2}\]

Recall that the moment vector describes the axis around which the body tends to rotate. Each individual component represents the tendency of the body to rotate around the specified axis.

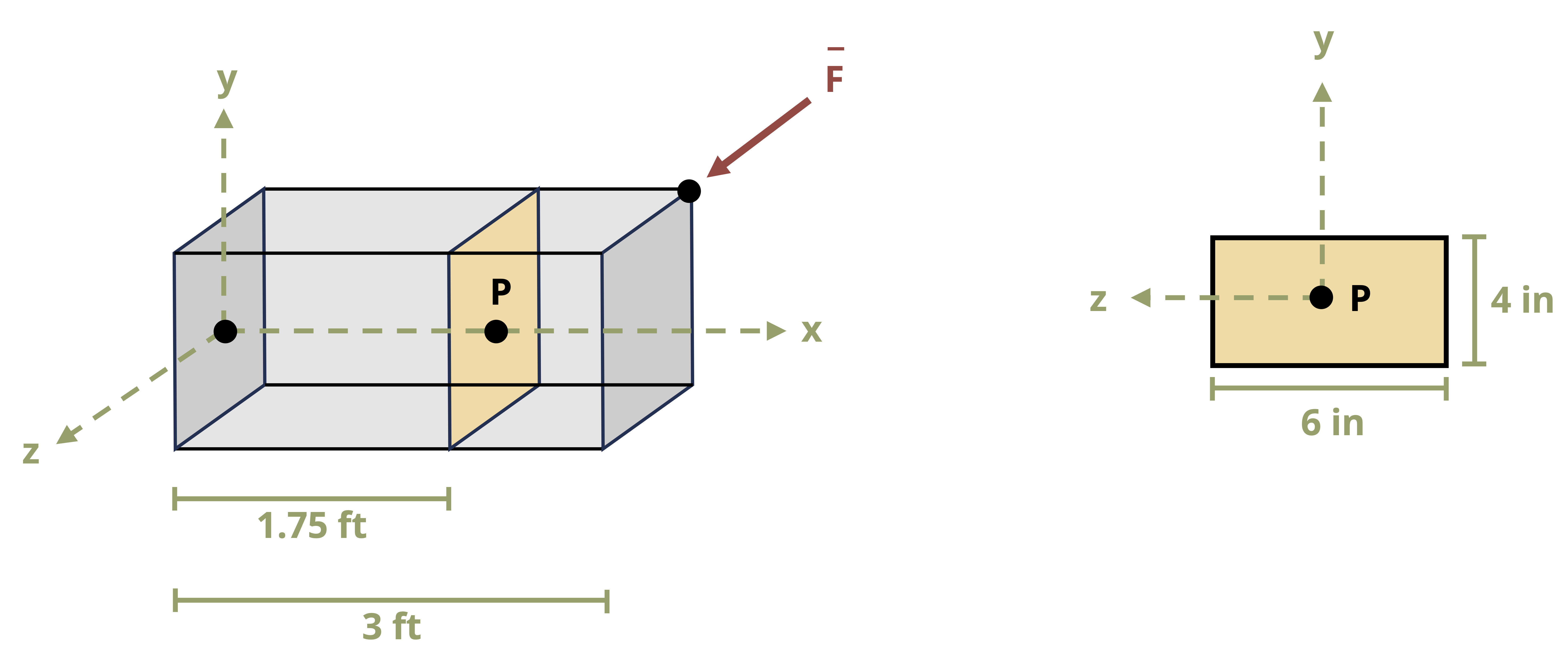

In 3D there are three internal forces and three internal moments (Figure 1.7). One normal force (Nx) is perpendicular to the cross-section, and two shear forces (Vy and Vz) are parallel to the cross-section. Two bending moments (My and Mz) act around the axes parallel to the cross-section, and one torsional moment (Tx) acts around the axis perpendicular to the cross-section. This textbook examines each of these loads.

Note that here the choice of coordinate system is arbitrary (as long as it is a right handed coordinate system). Loads are defined as normal, shear, bending, or torsional according to the effect they have on the body. For example, the normal force always acts in the direction perpendicular to the cross-section of the body and has the effect of extending or compressing the body. In the case of Figure 1.7, the x-axis is the axis perpendicular to the cross-section, so the force in the x direction is the normal force. If the axes or the body were oriented differently, the x component of the force could be a shear force instead of a normal force.

While summing the reaction forces in 3D is a straightforward process of adding forces in each direction, summing moments in 3D can prove to be more complicated. To sum moments, there are generally two options. One option is to use the cross product to calculate moments: \(\vec M=\vec r \times \vec F\).

1.4.1 Calculating Moments

Any position vector that goes from the point the moment is about to any point on the line of action of the force (F) will work for \(\vec{r}\) in the cross product. Considering Figure 1.8, we could say

\[ \begin{aligned}\vec{M_O}&=\vec{r_1}\times\vec{F}\\&=\vec{r_2}\times\vec{F}\\&=\vec{r_3}\times\vec{F}\end{aligned}\\ \]

Using the cross product to calculate moment will result in a vector expression for the moment equation that gives all three components at one time with the correct signs to indicate clockwise (negative) or counterclockwise (positive) rotation. The direction of rotation depends on the perspective, here taken from the positive end of the axis looking toward the negative.

The second option to calculate moments is to perform scalar calculations in which the sum of the moments about the x-, y-, and z-axis is calculated individually. To use this option, it might be helpful to recall several concepts:

The general scalar equation for moment is M = F⨉d, where d is the perpendicular distance between the point the moment is being taken about and the line of action of the force (see Figure 1.8). You can also use

\[M=Fr\sin (\alpha),\]

where

r = any straight-line distance from the point the moment is being taken about to any point on the force vector \(\vec F\)

α = angle between \(\vec F\) and the position vector \(\vec{r}\) that corresponds to the distance r.

Figure 1.8 shows various α and r pairs. Note that either α or its complement angle can be used because the sine of the angle is the same either way.

Forces do not cause moments about points they traverse or axes they act through.

Forces do not cause moments about axes they are parallel to—for example, Fx wouldn’t cause a moment around an x-axis no matter where the point is.

When taking the moment about a point, move the origin of the coordinate axes to that point to determine the distance between the axis and the force.

Given all the foregoing reminders, you can apply the following equations:

\(\sum M_x= \pm F_y * z \pm F_z * y\), where z and y are the distances from the x-axis at the point in question to Fy and Fz respectively.

\(\sum M_y= \pm F_x * z \pm F_z * x\), where z and x are the distances from the y-axis at the point in question to Fx and Fz respectively.

\(\sum M_z= \pm F_x * y \pm F_y * x\), where y and x are the distances from the z-axis at the point in question to the Fx and Fy respectively.

The ± is decided by the right-hand rule or visual inspection. As mentioned, when using visual inspection, judge the direction of rotation by looking from the positive end of the axis toward the negative end. A counterclockwise rotation is considered positive, and a clockwise rotation is considered negative.

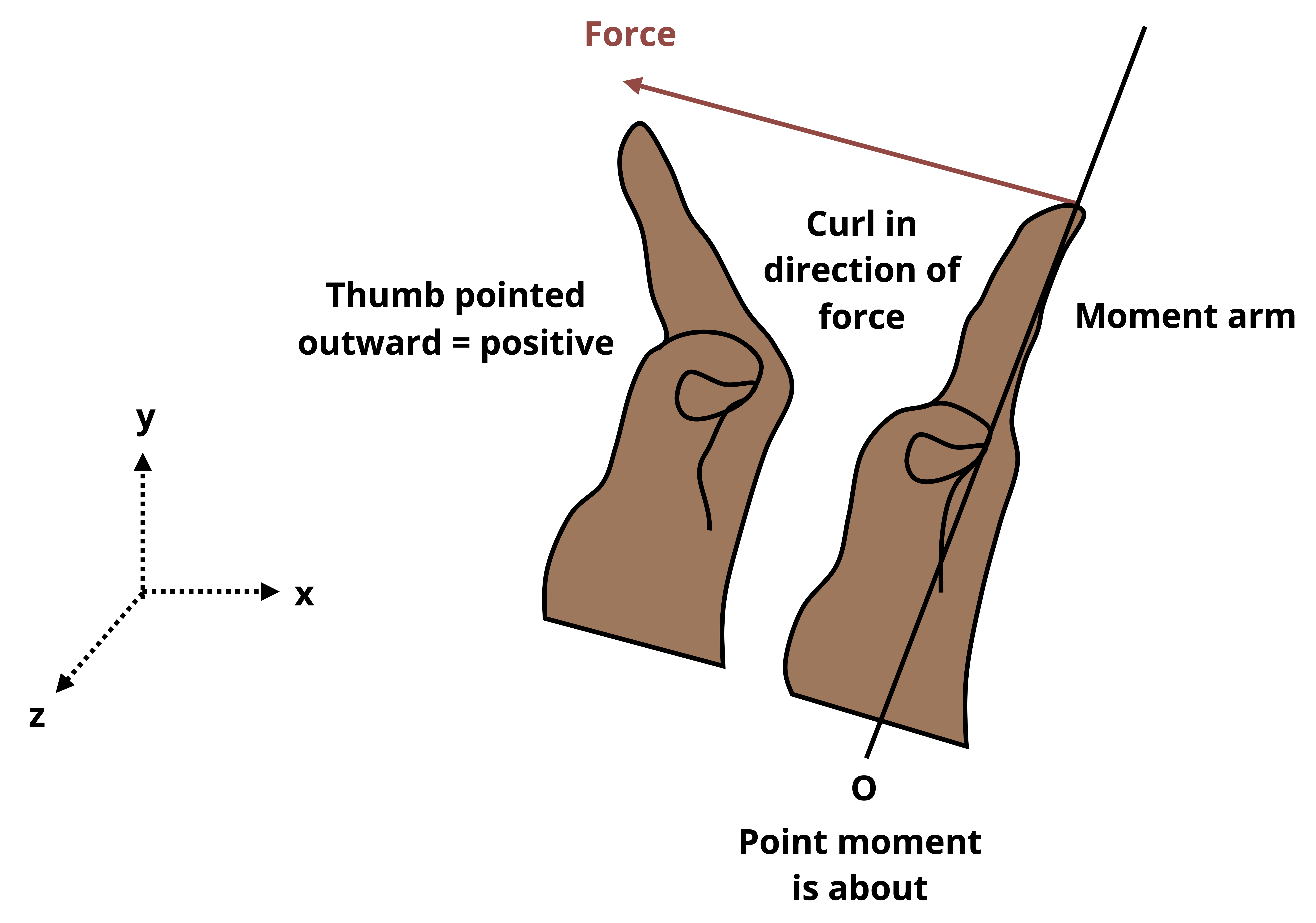

Take these steps to apply the right-hand rule:

Orient your right hand so that the palm is at the moment point and the fingers are aligned with the moment arm, extended to the force. The moment arm is the axis along which the perpendicular distance to the axis would be determined. For example, if finding Mx due to Fy, the moment arm is in the z direction.

The thumb is aligned with the axis of rotation—that is, with the axis around which the moment is being calculated.

Curl your fingers in the direction of the force. If to perform this action your thumb is pointed in the positive rotation axis direction, the moment is counterclockwise. If your thumb is pointed in the negative rotation axis direction, the moment is clockwise. Typical convention designates counterclockwise rotation to be positive and clockwise to be negative.

These concepts are further reviewed in Example 1.6.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license.